Watch Red Giant’s front page today for exclusive info on Colorista II!

Couple Things

After my Fetishists post, I was invited by Mike Seymour to join he and Jason on Red Centre to discuss in greater detail the points I raised. It was a welcome opportunity both to drill down on each of the specific issues, and to clarify a few things that some of the many comments seemed to miss—namely, that I chose my “fetishists” out of respect (so please, those of you with the pitchforks, put ‘em away), and that as crowd-pleasing as a “shut up and shoot” post can be, this actually wan’t meant to be one. The truth is, all your favorite filmmakers are fetishists, and you should be one too if you want your films to be their best.

Technology and gear are not the first things I think about when I think about filmmaking, but they do tend to be the first things I blog about. If “none of the tech matters, just make a movie” was the end of the conversation then that would be the end of ProLost. Talking tech is great, and nobody does it better than Red Centre, so please subscribe if you haven’t already, and give a listen to episode 66.

If you’d like to play the home game while listening, here are full-size stills of the image of Mike from the post, before and after color correction. These stills are pulled from 5D Mark II footage I shot of Mike in the Tsukiji Fish Market in Tokyo, and you can decide for yourself if it’s compression, 8-bit-ness, or an insidious combination of the two that makes it tough to brighten Mike’s face.

Click for full-res camera original image

Click for full-res, graded image

Click for full-res, graded image with some preprocessing

On the show Mike also mentioned that he’s embarking on a new fxphd DSLR Video course as a follow-up to the popular-but-aging session that he and I shot in Japan. This time, Mike has nabbed someone who actually knows what he’s talking about, none other than Tyler Ginter of the 55th Combat Camera Company. I look at a helicopter and think, “how can I put this in my movie?” Tyler looks at one and says “I think I’ll jump out of that with 90 pounds of gear strapped to me (including a 5D Mark II). Check out Tyler’s videos on Vimeo and stay tuned to fxphd for more updates.

In my last post I made a barbed remark about the Sony NEX-VG10, based on early reports that it only shot 60i (NTSC) and 50i (PAL). Turns out it may actually have a progressive mode, which would make the PAL version an option for filmmakers in PAL countries, or those in the U.S. willing to jump through the 25/24 speed-change hoops like we old fogies once did with the first DV cameras. Personally, I’ll wait for real 24p, the importance of which Sony, unlike Canon, cannot pretend to be unaware. Now that so many camera manufacturers are fighting to give us DV Rebels exactly what we want, I won’t be expending any energy on cameras that don’t.

And last but not least, if you’re not on Twitter, this might be a good week to start.

Not All is Crap in the World

I was having a bit of fun today combining the 3D Camera iPhone app (Alex Lindsay’s pick of the week on MacBreak Weekly yesterday) with Plastic Bullet (his pick a few weeks ago). After brunch at the amazing Brown Sugar Kitchen, I stopped by one of my favorite West Oakland sites: the concrete plant at Peralta and 24th.

No sooner had I started snapping my stereo pairs than I heard a loud “Hey!” In front of me, a dude in a hard-hat was pointing behind me. A guy in an orange vest was trying to get my attention.

Immediately I began subconsciously preparing my customary sanctimony. This is a public street. I’m just taking snapshots. It’s my right as an American. Today we celebrate our Independence Day. Etc.

(You may recall that I blogged a while back about a PDF you should print and keep with you called The Photographer’s Right, to help you with said sanctimoniousness.)

I turned to orange-vest man and he shouted over the truck noise “Hey, would you like to go inside? The angles are better! I’m the manager here, I can take you around!”

Say what?

Leave it to Oakland to continue to surprise even a guy who’s lived there for over ten years.

He led me around while I happily snapped, and I took his business card, expressing my sincere intention to use his location in a professional shoot if ever the right job came along.

There’s no conclusion here except that I thought I’d try to balance out all the whinging I do on this blog a bit. Not all is crap in the world.

Just the new Sony camera.

Seven Fetishists And Why They Should Relax

Mike Seymour: Bit Depth Fetishist

Mike Seymour of fxguide and fxphd loves his Canon 7D, but on the splendid Red Centre podcast he bemoans one shortcoming of its video mode more than all others combined: 8-bit files. Line-skipping, heavy compression, weird form factor? Mike’s not concerned about that nearly as much as he is the noise, banding, and crunchy chunky nastiness that he knows is lurking within those apparently lovely images, just waiting to pop out and bite him when he’s keying a sky or brightening a face.

Why Mike should relax: It’s just not that bad. It’s the compression more than the 8-bit recording that makes HDSLR video fall apart under stress. Get a good noise removal plug-in and watch your bit-depth magically appear to increase. And not every shot needs to be keyed. More professional photographers than will ever admit it shoot JPEG instead of raw. 8 bits is plenty if they’re the right eight bits.

Vincent Laforet: Gear Fetishist

Have you ever seen a photo of Vincent Laforet without something really, really expensive in the shot with him? Something black-anodized and wireless? Vincent loves the toys. He’s been using them to make awesome images before he fell in love with making moving pictures—he’d use film cranes to place SLRs in precarious positions on New York landmarks, for example. Now Vincent is reliably the guy who will strap a $4,000 camera body to about $300,000 worth of camera support gear.

Why Vincent should relax: More than anyone I know, Vincent could make a beautiful film with nothing more than a camera, a 50mm lens and a tripod.

Philip Bloom: Boke Fetishist

Sorry Philip, there are so many shallow-depth-of-field mavens out there to choose from, but your fanaticism for it combined with your keen eye and willingness to approach complete strangers on the street with a giant Zacuto rig sticking out of your chest like a spinal surgery patient have probably sold more Canons than their own marketing department has. Philip has made focus hunting into an artistic choice rather than a technical failing. And really, on a medium-close shot with one nice, sharp eye, who wants to be distracted by a crisp eyelash?

Why Philip should relax: Most movies are shot on 35mm film (roughly equivalent to the 7D’s sensor size) at about f/4. Some of my favorite shots of Philip’s have literally several things in focus.

Jim Jannard: Resolution Fetishist

Jim Jannard, founder of RED Digital Cinema, recently wrote “If 1080P is really ‘good enough’… then there is no reason for RED.” He’s bet everything that people care a lot about spatial resolution. Not satisfied to make a 4K camera, Jim announced a complete line of cameras for the pixel reductionist ranging up to a 28K monstrosity. To Jim, quality comes from sharpness and detail.

Why Jim should relax: The highest-grossing film of all time was shot in HD and then cropped for projection on screens the size of football fields. If you see a ‘scope movie that was shot in HD, you’re looking at an image only 800 pixels tall. Movies move. They have tons of motion blur, are rarely perfectly in focus, and they are watched by people who don’t have perfect eyesight in theaters that are manned by “projectionists” who focus biannually.

Roger Ebert: Frame-Rate Fetishist

Roger Ebert hates that wagon wheels go backwards. It drives him nuts. Years ago he saw a demo of Maxivision 48, a system that shoots and projects 35mm film at 48 frames per second, and he’s never forgotten how smooth it was. Like many, he decries 24 fps as a technological dinosaur, a holdover from a bygone era.

Why Roger should relax: With the advent of HD, it became easy to create digital moving images of high enough spatial resolution to pass for film (unless you’re Jim Jannard, see above), but at first we could only do so at 50 or 60Hz. HD video at 60 images-per-second inspired no filmmakers and no audiences—in fact, at the very Sundance I met Roger, a 60fps HD test shot by Allen Daviau was booed off the screen. It wasn’t until we hobbled our HD cameras to 24 that we could start making movies digitally. More frames-per-second is indeed smoother and more life-like. Just like video. Who would have imagined that audiences don’t want movies to feel more like daytime soap operas?

Jim Cameron: Depth Fetishist

I’m taking the hard road here by picking on a filmmaker I idolize, rather than the studio execs who see “3D” as just a longer way of typing the dollar sign. Jim uses the word I hate—immersive—to describe the effect 3D has on an audience. 3D is more “real” to him, more life-like.

Why Jim should relax: Jim has made some of the most immersive movies I’ve ever seen, and none of them needed an extra way to remind me that some stuff is in front of other stuff. 3D is an imperfect technology that has failed to win the love of moviegoers twice before. Movies work because they are larger than life. If you succeed at making them life-like, you run the risk of faithfully recreating the mundanity of the real world. Who would have imagined that audiences don’t want movies to feel more like plays?

Stu Maschwitz: Accessibility Fetishist

I flatter myself to be in the company of the above luminaries, but fairness demands that I turn the lens on myself. I am biased against expensive things. I’ll talk your ear off about how After Effects runs circles around Flame, and then instantly forget all your scathing rebuttals of all the things Flame can do that AE can’t. I get off on accessibility, even if I don’t actually access it. I bought a Canon HV20 the week it came out, calling it the no-more-excuses camera. Well I must have been wrong, because simply owning the camera didn’t cause a film to get made by me with it. Filmmaking is hard, and I sometimes get too preoccupied with finding ways to make it easier.

Why I should relax: Usually you do get what you pay for. A cheap, crappy follow-focus is just a non-refundable down payment on the good follow-focus you’ll eventually buy. And it’s the fact that filmmaking is difficult that makes it worth doing. Movies capture the efforts of a few and turn them into an experience for the many. Try hard, then try harder, then try harder still—and then look next to you at a filmmaker who’s trying even harder. Chances are you have a favorite director whose work has never been the same since they got famous enough to stop killing themselves making their films.

I kid because I love

In case it’s not abundantly clear: I admire every single one of these fetishists (well, except that last punk). But we can all use a little reminder now and then that movies work. They’ve transported us, fooled us, moved us, terrified us, and turned us on for a hundred years, all without any yet-to-be invented bells and whistles.

Movies aren’t broken. Stop trying to fix them, and go make one.

The State of Screenwriting Software

Every day, those of us involved in film and video post-production use some truly amazing software. Applications that transcode video, present complex changes in real time, and allow us to transform our images from footage into filmmaking. We manage terabytes of data, we reverse-engineer camera motion by tracking a million moving details, and we create entire worlds using nothing but mouse clicks.

So I’m always a bit surprised at how what seems to be such a simple task by comparison, putting words on a page, has perennially been handled in a way dissatisfying to so many writers.

Final Draft

Final Draft ($249 MSRP, $186.68 from Amazon) is the gold standard, if you take that analogy in the direction of gold being an outdated, unwieldy encumbrance, the continued practical significance of which is more imagined than real. Every “real” screenwriter uses Final Draft, and Final Draft’s .fdx file format is as close to a lingua franca as exists in Hollywood.

Final Draft is an essential tool for films in production because of its industry-standard revision management and compatibility with popular scheduling software, but over the years it has often been less than a joy to use for actual writing. If you used it on a Mac, Final Draft was always the app that made you most painfully aware of Apple’s willingness to start fresh with a new operating system. Final Draft sometimes felt like it was running in an invisible Macintosh Plus emulator ported to Linux and running in OS X’s X11 environment. Even as recently as version 7, Final Draft would only sporadically display screenplay text with an anti-aliasd font.

In fairness, the current version 8, which I was just forced to upgrade to thanks to Snow Leopard, is pretty good. It’s aesthetically minimal and feels like a good, native Mac app. But without wanting to discount the many complex features that Final Draft has under the hood, let’s remember that its main task is to place the letters that you type on the screen, and format them like a script—which, by definition, excludes anything not possible using a 100-year-old typewriter. Even in version 8, some aspects of this simple task remain buggy. I find that I can wind up with lower-case letters in a character name depending on the mood of the (admittedly quite handy) auto-complete feature. Similarly, I don’t know if it’s a feature or a bug that I can occasionally type lower-case letter into a Scene Heading.

But the thing that absolutely flabbergasts me about Final Draft is that, after all these years, it still reflects not one ounce of understanding of how screenwriters think about organizing their work.

Almost every screenwriting application has a “notecards” feature, where scenes are displayed as virtual 3x5” notecards that can be color coded, annotated, and rearranged. This is meant to to emulate the age-old screenwriter’s practice of avoiding actual work by dicking around with 3x5” notecards.

The problem is that Final Draft, like most screenwriting apps, assigns one notecard to each slugline, rendering the entire idea completely worthless. When writers use cards, they might break things down as far as one scene per card — but a scene usually contains multiple sluglines.

In this single page from The Bourne Supermacy (Tony Gilroy, Brian Helgeland screenwriters), there are five sluglines. Every page in this tense action scene is like this—cross-cutting between Bourne and the Treadstone assassin, moving from setting to setting, punching in for crucial details. In Final Draft, each of these sluglines becomes an index card:

Which is not at all how a writer would use cards. This entire eight-page scene would probably be one card called “CAR CHASE - KIRIL TRIES TO KILL BOURNE.” Or, for another writer, maybe the chase would be broken up into a few cards. BOURNE SEARCHES THE BEACH TOWN FOR MARIE, CAR CHASE - KIRILL PURSUES BOURNE AND MARIE, KIRIL SETS UP HIS RIFLE, etc.

The point is, sluglines and index cards have nothing to do with one another. In order for index cards to be of any use, they must be able to contain an arbitrary amount of screenplay.

Which brings us to…

Scrivener

I’m skipping over Movie Magic Screenwriter… oh wait, let’s not skip them entirely—just take a gander at this screenshot, which I just today pulled from their website. Wow. Anyway, on to Scrivener—the best screenwriting application in existence, and without even trying to be.

Scrivener ($39.95) is a Mac-only app developed by a frustrated novelist who wanted a better writing tool for himself. He does all the coding himself and you can expect a prompt reply from him on his company’s forum if you have ideas for improvements or if you’ve found a bug.

I know, crazy.

The catch is that Scrivener is a general-purpose writing app, with a few screenwriting features thrown in. It offers the basic formatting features, but makes no attempt at street-legal pagination, or managing a character list, or tracking revisions.

Which is so great, because it lets you Just Write.

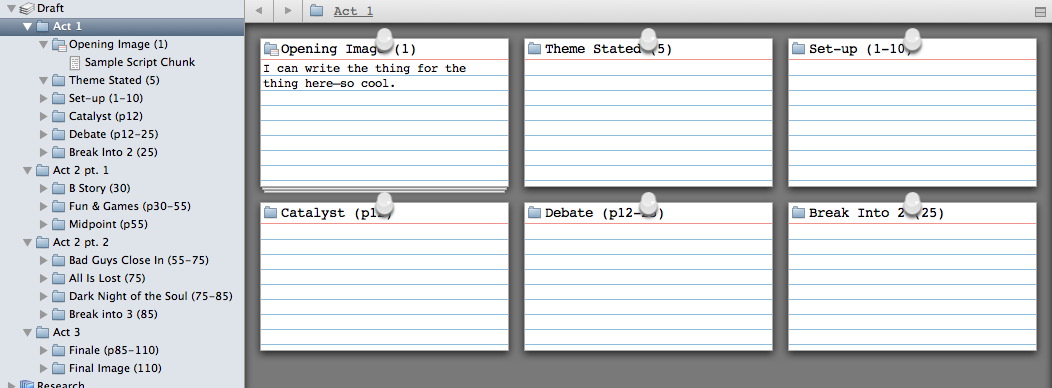

I could write a hundred love letters to Scrivener, but the one feature I’ll focus on today is the notecards. They are notecards done right. You can—get this—put as much or as little script in one notecard as you like. I never would have dreamed we even had such revolutionary technology.

Not only that, but you can have nested sets of cards. A card can contain more cards.

Whoah.

If that sounds like files and folders, then you’re getting it. In fact, the best feature of Scrivener’s notecards is that you don’t have to view them as notecards. You can always see them as a hierarchy of folders on the side of your screen.

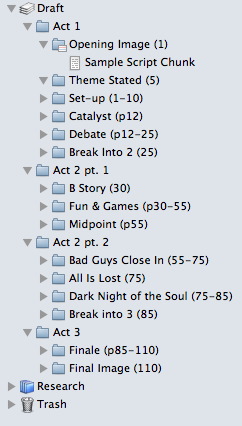

What you see here is the method of screenplay organization described in Blake Snyder’s Save The Cat. While everyone agrees on Acts I, II and III (yes, they do), different writers have different ways of breaking up what happens in each act. Scrivener lets you nest as many folders deep as you like, creating your own template, which you can load in at the start of a new project. At every nesting level, the folders can also be viewed as cards.

What this buys you is the ability to organize by cards at a high level and at a macro level—where cards become scenes. Real scenes, not sluglines. Scenes the way a writer thinks about scenes.

It’s so awesome that it takes a little time to get used to, but it’s worth it.

The only problem is that at some point, if you’re writing a real screenplay that will be read by real people, you have to leave the Scrivener party, put on a tie and maybe even pants, and show up for work at Final Draft. You need pagination. You need revision tracking. You need MOREs and CONTINUEDs (I guess). I respect Scrivener’s stated goal to not allow their creative writing app to sprawl into a full-fledged movie production tool. Scrivener is for writing. And man, it works. It’s almost like the guy who created it is a writer or something.

So I write this in the hope that Final Draft takes a stab at a folder or notecard system that makes one lick of sense. If you don’t, someone else will. In the meantime, I’ll continue to work in Scrivener for as long as I can before sobering up and looking around for where I left my pants.