If you’re reading this blog, you probably know the story — at least, you think you do. As Steven Spielberg began production on 1993’s Jurassic Park, he and Industrial Light and Magic’s Dennis Muren planned to execute the all-important visual effects component of the film’s prehistoric predators using tried-and-true stop- and go-motion animation1. But a bleeding-edge computer animation test convinced Spielberg and producer Kathleen Kennedy to risk it all on computer-generated dinosaurs, forever altering the course of visual effects in film.

It’s a story that had direct and momentous impact on my career, as I was a year away from graduating CalArts. Industry appetites for ILM’s digital magic would have the studio crewing up so rapidly that even a barely-drinking-age Stu was considered a viable hire. After contributing to both Jumanji and Casper, I was assigned to help out with the special edition re-release of Star Wars, where I lit, rendered, and provided rigging support for a Jabba the Hutt model built and animated by Steve “Spaz” Williams2 — the artist who created that industry-redefining test.

I distinctly remember a feeling of being thrown to the wolves. No one at the company seemed to know how to handle Williams, and I was an expendable pawn (who may or may not belong here) that they could toss into “the pit” with him in hopes of finalizing the single longest animation take in ILM’s young computer animation history. I had months to work on the sequence, which had me compositing in new footage of Boba Fett, puppet-animating Han Solo to step over Jabba’s tail, and hand-painting repairs to the Jabba renders to get the shots approved.

Working on Star Wars was, of course, a dream come true for this Gen Xer, even if I knew the material we were adding would never be a part of what I would consider to be the canonical version of the film. But it was working on Casper that put me in dailies every morning with Dennis Muren.

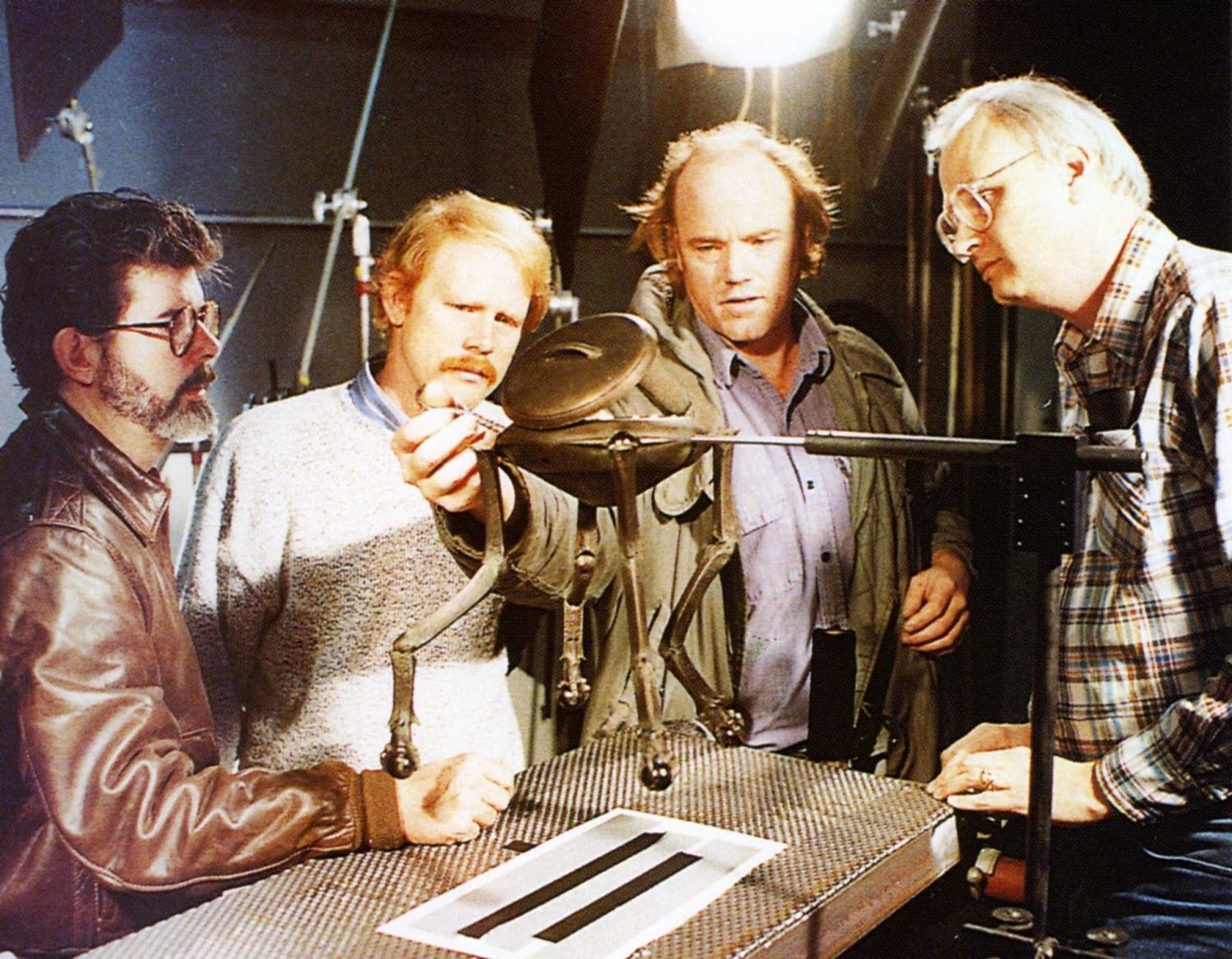

George Lucas, Ron Howard, Phil Tippet and Dennis Muren with a stop-motion puppet from Willow.

Muren was unequivocally my childhood hero, and working with him was as meaningful to me as getting my name in the credits of a Star Wars movie, or in the pages of Cinefex. I learned so much from watching him review dailies. The first time he complimented my lighting, I was ecstatic. Maybe I did belong here.

The Dennis Muren I knew emerged from Jurassic with an unmatched sense of how to incorporate the new frontier of digital VFX into ILM’s models-and-miniatures tradition. But his role in that initial test was always a bit unclear in the accounts I read and heard.

Williams with his fateful test animation.

Jurassic Punk is the deeply personal and profoundly surprising documentary about the man at the center of that pivotal — and controversial — moment in visual effects history. Director Scott Leberecht, my contemporary at late-’90s ILM, had unique access to not only Williams himself, but also his personal archive of memorabilia and never-before-seen footage. It makes for a compelling, informative, and deeply human story — complete with what, for me, amounts to a Shyamalan-level twist.

In Jurassic Park, Dr. Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum) declares of the ostensibly sterile dinosaurs’ miraculous ability to reproduce: “Life... finds a way.” Computer animation was inevitably going to crash through barriers and find its way into the film industry — and as with those fictional T-Rexes and Velociraptors, the way it happened was painful, and maybe even a little dangerous.

Jurassic Punk is a must watch for anyone who thinks they know the story of how everything changed in visual effects. It’s available today for purchase or rent on Apple TV.

As my readership mysteriously gets younger while I remain believably the same age, I feel compelled to address the reaction you might be having to this information if it’s new to you. If it sounds crazy to be considering King Kong-style puppet animation in 1993, just look at what ILM and Phil Tippet were able to do in 1988 with Willow, or even as far back as 1981 with Dragonslayer. Stop motion animation had been commanding the screen as recently as 1990 with Robocop 2. There's stop-motion in Terminator 2 (1991) that I bet you've never noticed. We were all watching puppets in theaters all the time back then, onions firmly tied to our belts.

Williams’s nickname is now widely understood to be a harmful slur, so I’ve included it here only once, for context.