Jonathan Poritsky has put together a lovely Fountain syntax highlighting package for Sublime Text. A great (and free to try) way to write your next movie in Fountain.

Production Audio is Ripe for Revolution

Dear companies that make production audio gear,

I love filmmaking. I love shooting. I love everything about the on-set experience.

Except recording audio.

When I’m filmmaking like a grown-up, I have someone else—an expert—handle dialogue recording. But often, it’s just me. Me and my portable audio recorder and expensive microphones and absolutely no frigging idea what I’m doing.

I’m a pretty smart guy. I truly get, in my bones, that poor production audio is the quickest way to sink an indie production. So I’m motivated to learn more about audio. I’ve tried, and tried. But it doesn’t stick.

My shotgun microphone has a little switch on it. That switch has two positions. One is the right one, one is the wrong one. You know what? It would be easier to just re-write this short to have no dialogue.

You’re probably thinking that I’m a lazy idiot. You might be right, but I think there are others like me too. Production audio is one of those fields populated by experts who have long forgotten what it was like to ever not have a complete grasp of hypercardioid patterns, phantom power, and 60Hz hum. To those experts, we who scratch our heads at those terms must seem so thickheaded. But trust me guys, this stuff you know forward and back is actually quite maddeningly opaque from the outside.

Audio is hard. And everyone who understands it seems to have forgotten that. So they suck at explaining it. And so here I sit, recording bad dialogue with many hundreds of dollars in gear, feeling like an idiot.

Or a tremendously underserved market.

The Revolution of Easy

Video is hard too. But people are working like crazy to revolutionize it so that people unable, unwilling, or just plain uninterested in becoming video or photo experts can still make great-looking images. 1080p cameras fit in the palm of your hand—and then employ elaborate stabilization methods to fix the jitter caused by their own weightlessness. Your iPhone merges multiple exposures into a single HDR the moment you press the virtual shutter button. And I, for my part, work hard daily to design color correction tools that make sense to anyone who has ever seen a lens or a ray of light. When I’m at my best, I can make anyone feel like a color correction expert. But I know I can do better. We’re all working really hard on the problem of helping you make the images you want.

Is this happening in audio as well? If it is, I don’t see it. I see evolution, not revolution. I see better tools for experts, not tools designed to make us idiots feel like experts.

Being a video nerd, I know that the imagery from that pocket HD camcorder isn’t stellar, and that the HDR capture from an iPhone isn’t as good as an exposure merge from a DSLR. But I also recognize that these consumer toys are helping people capture much, much better images than the enthusiastic amateur has ever been able to.

There’s a huge, untapped opportunity to do the same for audio.

Abuser Interface

Have you ever navigated the menu of a Zoom H4N? It’s like playing a Chinese knockoff of Tetris on a Gameboy that was run over by a car.

Like every filmmaker I’ve ever met, I own an iPhone. Build your portable audio recorder around that. Make a great app to control it. Sell a kit with a badass shotgun mic in a shockproof mount, one of those furry sock things, and a connector that connects to my iPhone (which you already know how to do).

But don’t just use the iPhone as a better screen for your crappy User Interface. Don’t even think it’s enough to use it as a platform for new, sexier UI. Put that little pocket supercomputer to work to make my life as a filmmaker easier.

Rate the quality of my incoming audio on the screen, live. Warn me when I have a bad echo, or background noise. Suggest fixes. I’ll move the mic around as instructed and watch the quality level change, and then stop moving when it’s great.

Listen for me saying the word “check” and set the audio levels automatically when you recognize that word. Flash an alert on the screen if you detect a hum. Or an airplane flying overhead.

Some Sony cameras have a mode that automatically snaps a photo when the subject smiles. Step up the tech, audio nerds. I know you can do this stuff.

The Wire

A good wireless lavalier kit goes for roughly four times the cost of an iPod touch, and suffers from radio interference and complexity. Build me a lapel mic that wires to an iPhone/iPod in my actor’s pocket and you just saved me endless headaches and hundreds of dollars.

Heck, I’ve never met an actor who didn’t have an iPhone. I’ll install the app on their phone and save a few more bucks. That way I can actually keep their data connection on, and your app can send recording levels and other reports to my phone, so I can monitor and control multiple mics on one touchscreen. Start and stop them all simultaneously with the push of a button (like GoPro already does with their pocket HD cameras). And let my intern log into the same account and tag the incoming audio files with slate info and other useful metadata, like the name of the character being recorded—all while we work.

Know that I have PluralEyes

Post isn’t easy, but it’s much more forgiving than production. You have time to correct your mistakes, and you have some truly magical tools at your disposal, such as PluralEyes. Recently acquired by my friends at Red Giant, this technology aligns sound and picture tracks based on audio waveforms. Which means that you can automatically sync your high-quality production audio with your video and its crummy scratch track from the camera mic.

This would be amazing if it wasn’t already so ubiquitous. The same tech is built-in to Final Cut Pro X. So build your audio tools assuming I have this auto-magical post-syncing capability. I don’t want or need a cable running from the recorders to my camera. Use your awesome tech to keep me nimble.

You could team up with Red Giant and other developers to make that software work even better. Make an iPad slating app that emits a special coded beep that contains the audio equivalent of a QR code. Every beep is a unique timecode signature. Post-production software could recognize that and sync dailies easily.

Or do you even need that? Aren’t all of our devices syncing to the same clock anyway? Aren’t there some amazing affordances possible based on that simple assumption?

Do Better

This is what I cam up with in one evening of pounding keys. But as we’ve established, I’m a lazy idiot. You’re the experts. Come up with stuff that makes my ideas seem trivial and silly.

I have money. I’d love to spend it on audio gear that makes me feel like the expert I’ll never be. I know that, like the vast majority of photographers and videographers, I’ll achieve much better results with revolutionarily easy tools than with expert gear. Democratize the one aspect of filmmaking that a new whiz-bang camera every few weeks can’t touch. The first one to do it will make all the others look like idiots.

I’ll be so happy to hand over the title.

Thanks to @felliniflex for pointing out the Fostex AR-4i.

The response to this post has been fantastic. Mostly positive, along with a few valid criticisms the validity of which only underscore the reasons I felt compelled to write it in the first place.

But a few of the loudest disagreements seemed based on misunderstandings of my points. In my effort to be succinct, I may have left some room for such misunderstandings, so here are some clarifications:

Computers Can’t Do the Creative Work of Miking/Recording

I agree. I never said that I wanted the device or app to make the creative/craft decisions for me about where and how to mic. I suggested that the devices could use signal processing to give me some help in evaluating my sound, and that digitally-linked, self-sufficient units could require less fiddling with wireless technologies.

None of the video features I described by way of comparison tell you where to point your camera. I’m not for a second suggesting that the audio recoding process shouldn’t be manual and creatively authored by a real, thinking person. I’d just like the hardware to help that person, and not require them to be an expert in order to achieve decent results.

Good Audio Gear Must be Expensive

I agree. When I said “I have money,” I could have elaborated and been crystal clear: I have and will freely spend money on audio gear. What I lament is that after all the money I’ve spent, I’m still producing bad results. If any of the tools I imagined above hit the market, I would not expect them to be cheap. I would happily pay good money for gear that helped me achieve good results.

My assertion is that a non-pro will get better results from easy-to-use, not-so-super-pro gear than they will with the pro-est of the pro gear that they don’t know how to use properly.

Why the Focus on iOS?

I realize that you might not love everything Apple does, or how they do it. But movie sets are lousy with iPhones. It’s a practical choice—but not the only one. Remember these are just suggestions. Feel free to suggest something better. “Not Apple” is not a suggestion.

I never proposed that the iPhone—or whatever—should be performing the A2D duties, or that microphones should be plugged directly into its headphone jack. My point is that every crew member on even the lowest-budget production is likely to have a connected, touchscreen device that could be leveraged to make life better.

I Still Disagree

Adobe Anywhere

Promising!

Update

on 2012-09-05 19:25 by Stu

The press release lists After Effects among the supported apps.

Final Draft Writer vs. the Innovation of Less

Final Draft, Inc. released their much-anticipated iPad screenwriting app this week. Called Final Draft Writer, it promises complete compatibility with the desktop app, and near-feature-parity as well.

We’ve known this was coming for a while. As Final Draft, Inc. was beginning work on this app, they solicited the opinions of screenwriters on what capabilities it must have. To no one’s surprise, we wanted it all—the full Final Draft experience. And faced with a pile of surveys with nearly every box checked, Final Draft, Inc. hunkered down and did exactly what we asked for.

First Impressions

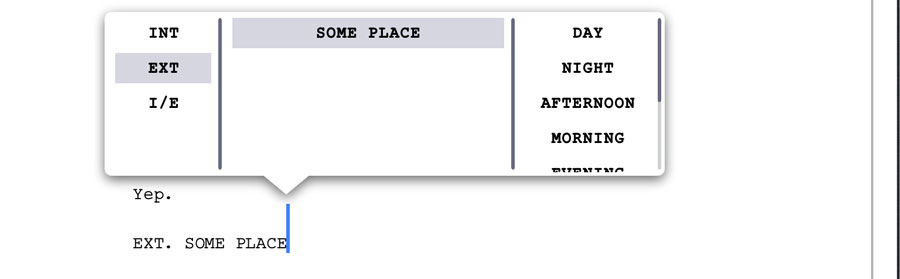

The touch interface for drafting a Scene Heading is nice. And there’s a clever extra with the omnipresent scroll bar—as you drag it, a callout displays not just the page number, but Scene Headings as well. Although I don’t believe in Final Draft’s reliance on Scene Headings as the sole organizational tool for writers, this is still a welcome touch.

The app is full of details like that—details that show this to be a sincere and earnest effort to create a best-in-breed mobile screenwriting tool.

On the negative side, the app’s performance is not so great. Writer promises a perfect match to Final Draft’s industry-standard pagination, revisions management, and scene numbering, as well as some nifty bells and whistles, such as character highlighting and colored rendering of colored pages. All of this would seem to come at the cost of a noticeable lag as you type.

Final Draft Writer supports Dropbox, but in a manual push-and-pull kind of a way. If you are accustomed to apps that sync with Dropbox automatically as you work, Writer’s method will feel antiquated and un-iPad-like.

The Price

John August told Macworld:

“I’m rooting for Final Draft (and Scrivener, and Movie Magic Screenwriter),” August told us, “because I want to make sure there’s always a market for high-end professional screenwriting apps. The race to the bottom in software pricing is dangerous.”

I couldn’t agree more. There’s nothing wrong with Final Draft charging $50 for this app ($20 off until the end of September). Anyone who needs it can afford that. Conversely, if it seems expensive to you, then there are numerous other options.

Numerous Other Options

Of them, I would say that the recently-updated Scripts Pro and the feature-rich Storyist seem to have broken away from the pack as clean and reliable, FDX-compatible screenwriting tools for iOS.

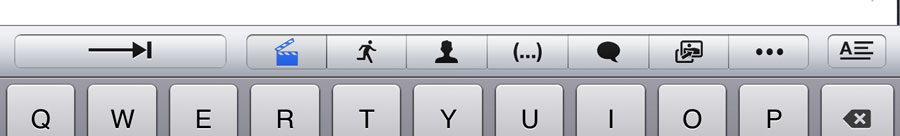

It’s hard to imagine typing a screenplay without relying on buttons like these. Unless you’ve ever seen a typewriter.

But when I look at these apps’ pop-up menus or little rows of buttons for assigning element types, I no longer see the most minimal screenwriting UI I can imagine. With Fountain, the notion of choosing a “container,” and then filling it with text, is obsolete. Instead of constantly reaching for the mouse or touchscreen to declare what you’re about to write, you spend all your time with your hands on the keyboard, just writing it.

A Fountain-format screenplay in Byword for iPad

Screenwriting Without the Tab Key

The innovation of the iPad was that it was a computer that intentionally did less. Like a fixed-gear bicycle or an electric car, it allowed us to more easily do 90% of what we needed to, by saving us from wading through a phalanx of features designed for those occasional 10% requirements. For possibly the smallest imaginable example: the iPad’s touch keyboard lacks something most screenwriters use a thousand times per day: a Tab key.

There’s no “innovation of less” with Final Draft Writer. It ticks every one of the feature checkboxes those surveys reported. The result is impressive, but it feels like 10 pounds of app in a 1.5-pound bag. And like every other iPad screenwriting app I’ve seen, it grafts a Tab key onto the iPad keyboard layout.

On the other hand, if you want to write a screenplay on your iPad without all those annoying screenwriting features getting in your way, consider Fountain, along with a minimal text app such as Byword, Elements, or Writing Kit. Screenwriting without the need of a Tab key is a rather liberating experience.

The name of Final Draft’s iPad app is actually oddly apt—it invites the question: Are you a “Final Draft writer,” or a screenwriter?

Because the days of those notions being synonymous are rapidly fading to black.

Update

on 2012-09-13 04:02 by Stu

According to Final Draft, this constitutes a “rave review.”

Blackmagic Cinema Camera

The NAB 2012 announcement of the Blackmagic Cinema Camera (which folks are thankfully calling simply “the BMC”) from Blackmagic Design, the company that makes delightful video doohickies and acquired industry giants Da Vinci and Teranex, revealed a few interesting things:

- We are living in the “Chinese curse” age of cameras.

- In other words, disruption is the new norm. I’m not sure if there’s a static “game” to “change” anymore. So maybe we could all agree to stop saying that?

- Prolost is not a “camera blog.”

The so-called Chinese Curse goes “May you live in interesting times,” which certainly describes the landscape of digital cinema offerings available today. Apparently, we self-sufficient film folk now constitute a market worth serving directly. Where once we bent ill-suited cameras to our cinematic purposes (first all-in-one camcorders with tiny sensors and abusive automation, then DSLRs with near-accidental video functionality), now we can’t go a month without another “revolutionary” filmmaking camera competing to offer us something amazing at a previously unimaginably low price.

The question is, will these purpose-built offerings, such as the Kickstarter success Digital Bolex, the Sony FS–700, the 4K-ish Canon 1D C, and the KineRAW-S35 cure the DV Rebel of the urge to repurpose consumer cameras for their filmmaking efforts?

Blackmagic has seemingly (nearly) hit the “3k for 3k” target that many hoped Red would deliver, at a Micro–4/3-ish sensor size wandering between the 2/3” sensor many associated with the notion of a 3K raw camera and the increasingly ubiquitous and affordable Super 35mm size. If that seems like a decent deal, it’s worth noting that every BMC ships with full licenses of Resolve and UltraScope.

I was pretty busy when this camera was announced, but that’s not the only reason I refrained from comment at the time. I’ve gotten a bit weary of writing about unreleased cameras. Red has taught me to comb my writing for phrases like “the camera will have” and replace them with “the camera is said to feature,” and pretty soon I feel like I’m writing about nothing. But late last night, cinematographer John Brawley posted five test shots from a “production model” of the BMC to a brand-new Blackmagic forum. Brawley encouraged us to download the Cinema DNG sequences ourselves and have a play—so I did.

I love big-sensor digital cinema. I love shallow depth-of field. I’m fond of pointing out that sex appeal trumps tech specs every time. The interesting thing about the footage from this not-quite-cinema-sized sensor is that it is sexy. Not because of fetishistically shallow depth-of-field (although Brawley handily demonstrated that focus control is eminently possible with the BMC and some nice glass), but because it’s raw. I graded these shots in Lightroom 4. They came in looking a touch overexposed. I easily recovered the highlights and pushed these shots all over the place, but they never broke. After years of shooting with Canon HDSLRs to massively-compressed codecs, the rich neg offered by this little camera was beyond refreshing.

It’s easy to imagine that Blackmagic chose the smaller sensor to keep the price of the BMC down. It’s easy to get caught up thinking that maybe next, they’ll release a true Super 35 version of this rig. Or that the KineRAW at $6K might be worth the extra cost over the BMC.

But the challenge that befalls camera manufacturers is not to build the “perfect” digital cinema camera. It’s to capture the hearts and minds—and wallets—of filmmakers as much, or even more, as the wrong camera for the job keeps doing.

I think the Blackmagic Cinema Camera might just do that.

The Blackmagic Cinema Camera is available for pre-order now from B&H.