This is a follow-up to last week’s post on the Light L16 camera, a computational camera that claims unprecedented big-camera performance in a small-camera form. Light launched a pre-order campaign last week, with intent to ship the L16 in late Summer 2016 — and yesterday they announced that the pre-orders have been so successful that any placed after this Friday will ship later, in Fall.

On Monday, I visited Light’s offices in San Francisco. I saw their working prototype, their mock-up of what they intend to ship, and had a delightful and thorough conversation with their co-founder and CTO Rajiv Laroia.

I write this with some circumspection, as I look back with some regret in participating in breathless speculation about previous camera announcements that ultimately fizzled. But Light shared some interesting information with me that hasn’t been available elsewhere, so I felt I’d be doing a disservice not to share it here.

So here’s what we talked about.

These guys are the real deal. That’s maybe the most important takeaway from my visit. I’m impressed with what they’re up to. I still have a few concerns, but these guys are smart, they care about the right things, and from what I can tell, they have a sound plan. Check the About page on their site — they’re being very open about who they are and how much money they’ve raised.

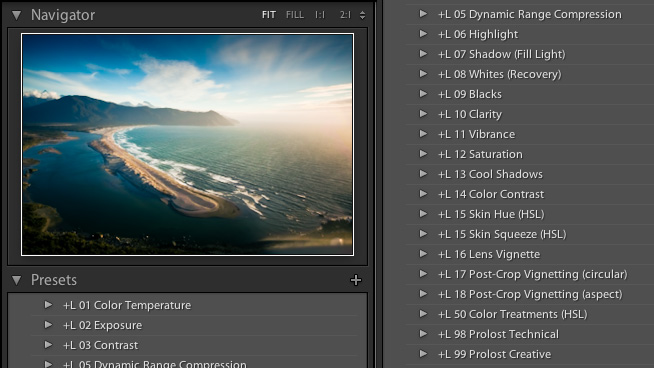

Speaking of “open,” they showed me all the blueprints. Using a 3D-printed model of the insides of the camera, they showed me the five direct-firing 35mm-equivalent cameras, and the 70mm- and 150mm-equivalent cameras that surround them on their sides, shooting through mirrors. You can probably figure out which are which in the photos. There’s a lot of thought to the layout, including accommodations for rolling shutter, and even placing closest to the handgrip the lenses least likely to impact image quality when occluded by a stray finger.

They showed me the mockup, which you saw in their promo video. It’s neither small nor big, and felt good in my hand. They also let me try a detachable oversized handgrip that I hadn’t seen on their site, which helps with balance and is planned to contain a larger battery as well. VP of Marketing Bradley Lautenbach told me that this grip will be included with the pre-ordered cameras.

They showed me the functional prototype — which still requires lots of help to do its work, but is ambitiously similar in size to the mockup.

Rajiv Laroia is an imposingly smart guy (you met him in this video), yet was more than generous with his time, and open about the challenges that face his company. He understands optics, and has no interest in defying the rules thereof — rather, he’s excited about harnessing them in new ways.

All in all, I was impressed.

They don’t need our money. They have $35M in investment and, in a detail absent from their site, are partnered with Foxconn for production of the L16. The $200 pre-order is designed to measure demand, so they can both begin a dialogue with a commited community, and set up their supply chain accordingly.

Speaking of supply chain, Foxconn makes iPhones. The L16 is a camera with high-end photography aspirations that will be built on mobile phone production lines, which is unprecedented. Rajiv stressed that the “why now” of the L16 is that, in the past five years, there has been a revolution of quality for cost in these smartphone camera modules. The quality is so good that the tiny plastic lenses in the L16 prototype are diffraction-limited, meaning they can resolve as much detail as the theoretical limit imposed by their size.

Which is why I was wrong about superresolution. I theorized that the L16’s megapixel claims were a product of interpolated resolution, but Rajiv set me straight on that.

The crazy resolution comes from tiling, which means those little mirrors actually move. When you shoot at the 35mm equivalent zoom, the five 35mm cameras fire, as do the five 70mm cameras. The 70mm cameras are oriented by their mirrors to tile the FOV of the 35mm cameras — one for each corner, and a fifth in the center.

The result is fused (not tiled) into a combined, simulated exposure.

An L16 photo at 35mm is made up of five 35mm (equivalent) images, plus five 70mm image tiles, all taken from slightly different perspectives.

What happens when you shoot at 150mm?

The mirrors angle the fields of view of the 150mm cameras to overlap completely, and the 70mm cameras fire too.

The details about the individual cameras that make up the Light L16 have been right there on their own web site since launch.

Video is a matter of bandwidth, storage, and heat. And processing time. The L16 will generate about 50 megabytes of losslessly-compressed material per exposure. Light could aspire to do that 24 times per second, but the camera would have to look a lot different to accomodate the requisite processing power and storage. Light is not setting their sights there just yet. For now, 4K video comes from a single camera — but which camera is determined by your zoom choice, so you should expect 4K at any focal length from 35mm to 150mm.

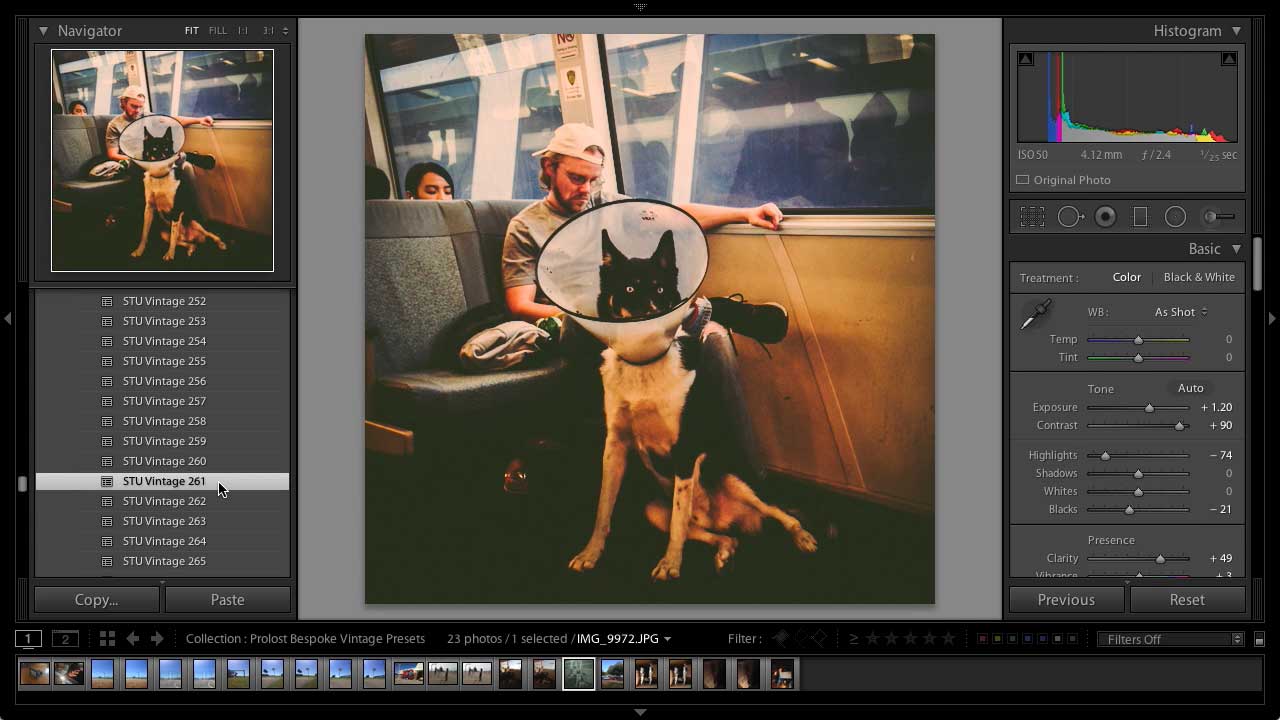

They really want to work well with Lightroom, which is great. Light’s software (which does not exist yet as shown in the video) is promised to output DNG files, but they know that closer integration would be better.

You do focus the L16. All the lenses focus together. Your range of refocusing in post centers around the focus point you selected when shooting.

Close focus distance depends on zoom, just like in reality. Expect about 10cm minimum focus at 35mm, 40cm at 70mm, and 1m at 150mm. Let’s not hold them to these numbers, but it’s nice to know.

The cameras use electronic shutters. Which means the L16 will be prone to rolling shutter artifacts, just like your phone. In other words, it’s probably not something to worry about. Long shutter durations are created by accumulating multiple readouts of the sensors.

Light needs light. The L16 is a light-gathering device. Thats why it’s as big as it is — just like my Canon 50mm. There is an ISO, but no control of aperture. They may promise great low-light performance, but you’ll make better photos with more photons.

There’s a depth map, and you can have it. The L16 outputs a depth map of the scene, and Light expects folks to use this to great effect in post processing. A high-quality depth map makes it easy to cut out foreground objects, or insert imagery into a photo.

The sample images on their site are not representative of the final quality they intend to ship. They know their gallery needs work. They realize the images are biased toward showing off sharpness, punch, and resolution, rather than meaningful refocusing and DOF-simulation. They know their low-light example isn’t great, and they know they’re not yet impressing anyone with the dynamic range.

As one might imagine, they scrambled to get these images shot with the prototype in time for their launch. Many features are not implemented yet in the prototype, most notably varying the exposure from camera to camera for single-shot HDR capture. This should improve dynamic range dramatically.

They know they need some soft-focus, non-blown-out sample shots, and they plan to shoot some.

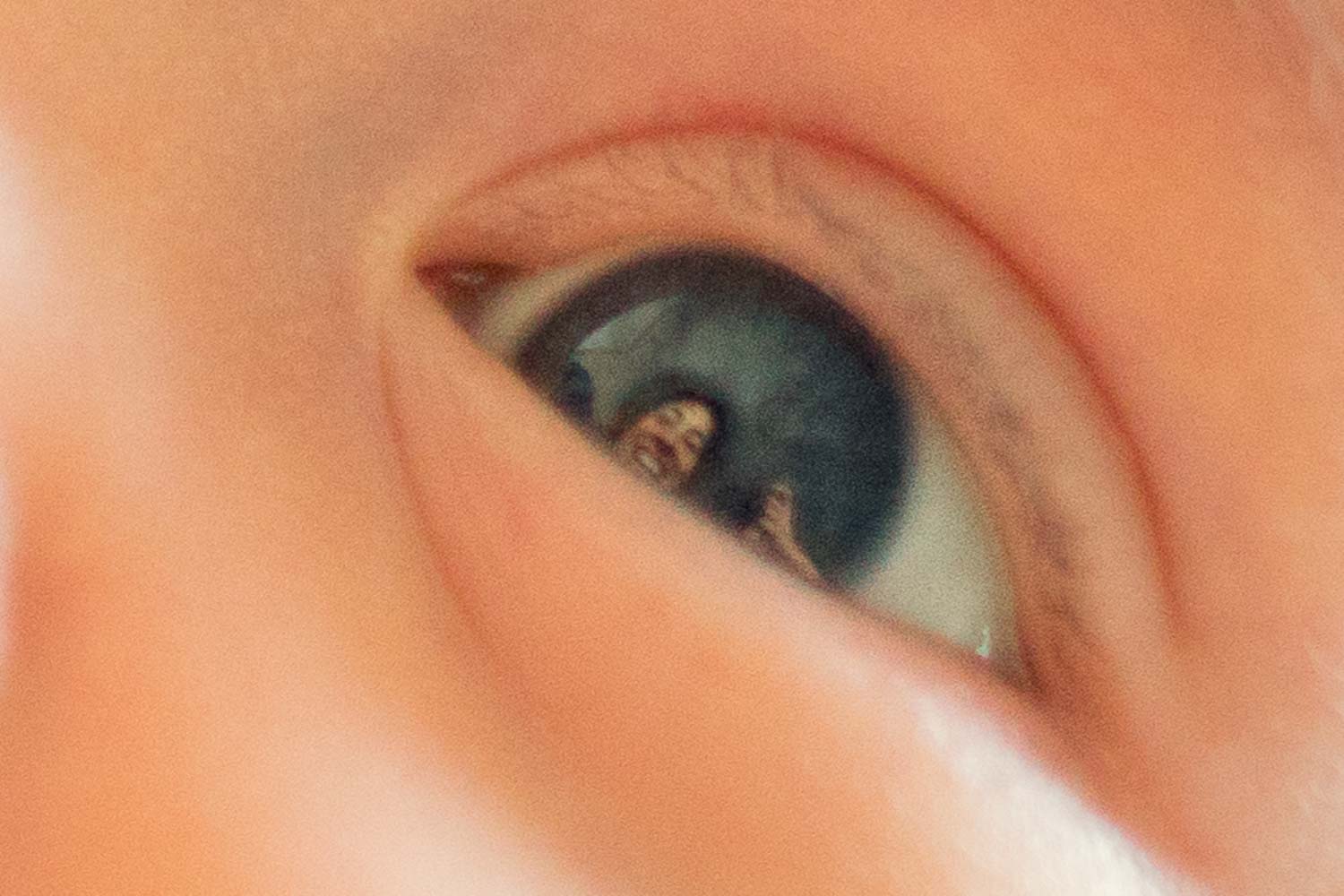

But I’m still worried about their ability to make super sexy shallow DOF photos. I brought my Canon 5D Mark III with 50mm F1.2L lens along, hoping maybe I could do the Pepsi challenge between it and their prototype. That didn’t happen, but we looked at some ƒ/1.2 photos I’d shot recently and spent a good deal of time talking about that shot from Nocturne. We talked about what makes for pleasing boke, and what kinds of creative possibilities emerge when boke is simulated. Rajiv confidently assured me that they could do everything a real lens could — but he also repeatedly referred to my ƒ/1.2 photos as “corner cases,” which is engineer-speak for “not the problem we’re solving for” — and that concerned me greatly.

Light claims the L16 (mockup shown here on the right) will do everything the full-frame Canon 50mm F1.2 rig on the left does, and more.

I pushed back and told him what he already knew — that when I buy a lens that says “F1.2” on it, I’m not spending $1,500 to shoot at ƒ/4.0. Photography is all about corner cases. We buy full-frame cameras and fast glass so we can push them to their extremes. The cake I want to have-and-eat-too with the L16 is the shallow DOF of my Canon, with the promise that I’ll never miss a shot due to focus.

A portrait I made at 50mm, F1.2 on Saturday. This is the kind of image I'd like to see on Light's L16 gallery page.

The biggest complaint I’ve seen about Light’s marketing is that they talk about ƒ/1.2, but don’t show it. Ironically, their own site is full of shallow-DOF photography with sexy boke — but it’s all the shots of the camera, not made by it.

The biggest risk I see facing Light with the L16 is that they’ll be able to produce perfectly acceptable photos with it.

We can already do that with our telephones. The challenge is clear: They need to bring the sexy.

There are so many more possibilities to come. The potential of cameras like this is mind-boggling. The depth map could well be so accurate that you could usefully measure objects in a photo. You could accurately place 3D objects into an L16 photo, with automatic occlusion. It’s an ideal tool for lightweight 3D scanning too — extracting a decent 3D model from a depth map and corresponding RGB data is trivial, and technology exists to merge a few such samples into one very nice textured 3D model.

But back to photography: When it comes to simply processing your photos, much more than simple selectable focus is possible. You could design your own boke pattern. Create a plateau of focus in an otherwise shallow-focus shot. Tilt or even bend the plane of focus to hold two sharp eyes at ƒ/1.2, or simulate a tilt-shift lens. Because you can center the synthetic aperture anywhere on the virtual imaging plane (just like Lytro), you can do parallax tricks, or render a stereo pair of images from a single shot.

The L16 may or may not be able to make photos as appealing as those I routinely make with my bulky, expensive Canon rig — but it may not have to either. It might carve out an important niche for itself as a camera that is much more than just a camera.

But I hope it does more than that.

Last point: We’re not done. They’ve invited me back for another visit. This time, we’re going to take some pictures.